"Why do our Christian brothers and sisters in the United States hate us?"

I was only just old enough to overhear this question when it changed my life. I suppose that people change for a lot of reasons and in a lot of different ways—certainly I have. Sometimes we encounter someone or learn something that changes us in a flash. One moment we were convinced of one thing and were living our lives by it and then—bam—we learn a missing fact or meet someone new and are convinced almost instantly that we had been wrong, that a different proposition is actually true, and our lives change. But most of the time I don't think it works like that. I think most of the time we have these experiences and they settle in and start to work on us slowly. If our significant changes in the way we are oriented towards our world can be compared to landslides, then most landslides start with pebbles bouncing down the hill; they bring a few other pebbles with them and those pebbles loosen bigger rocks. Now the hillside is less stable and then there is a rainstorm and then, in what seems like an instant, the whole vista gives way and changes irrevocably.

I have experienced a number of these shifts in my life; I consider it a sign of health. After all, I know more now than I did when I was younger, and I have picked up habits of reasoning which (I hope) have improved my capacity to analyze what I know. Additionally my character has been formed through relationships and through my reading; the weight things have with me has shifted and—I hope—grown into a more accurate reflection of the real value of the world.

The question I opened with—

Why do our Christian brothers and sisters in the United States hate us?—is one of the pebbles, possibly the first pebble, in the what became the landslide which marked my ultimate rejection of politically conservative US Christianity. Of course, few quotes are meaningful without context and the context for this one is critical. I was in (I think) seventh grade at the time, and the question was on the lips of a Palestinian Christian. He asked the question to my Dad after dinner.

In fact it took a lot for me to hear that question. My family moved to Turkey when I was seven years old—my dad was offered and accepted a position at a joint venture company in Ankara—and I lived there till college. While I was there my parents helped to found the

International Protestant Church of Ankara and have been involved in its leadership ever since. When I was around twelve my parents planned a family vacation to tour Israel and Palestine. In the course of planning the trip, they spoke with some fellow church members of ours who were Palestinian Christians studying at one of the universities in Ankara. One of those students was from Bethlehem and was determined for us to go and visit his family while we were in the area. At that point in the mid-90's the Israel/Palestine conflict was in one of its hotter periods so American visitors had been warned against going to Bethlehem. Our friend the college student gave my dad some instructions about how to ensure that our car would be protected by Palestinians and insisted that we visit. You can imagine that for a twelve year old, this was the very height of international adventure. We were going to act on privileged information, put the right symbol in the dashboard of our car and be granted special access to visit Bethlehem at a time when most Americans were afraid to go.

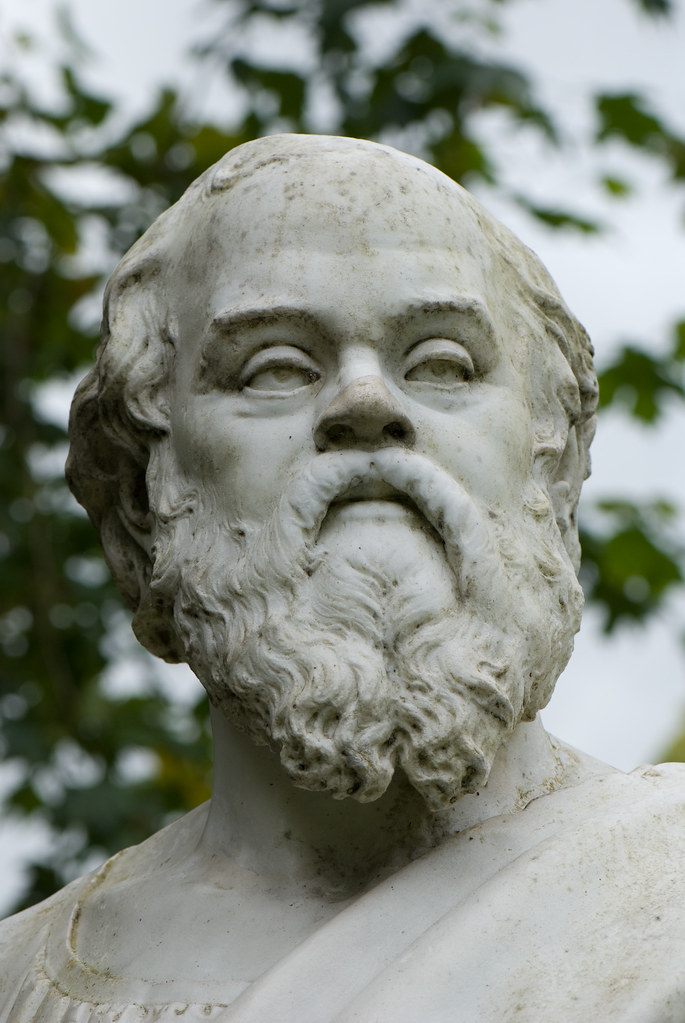

|

| The Church of the Nativity |

And all of it worked. We drove into Bethlehem, visited the Church of the Nativity, and had a lovely ham dinner with a charming and hospitable Palestinian family. The delight of the ham particularly stuck with me because, as an American Christian living in Turkey, I didn't get to enjoy pork products all that often and, since we were vacationing in Israel for most of the trip, I hadn't been able to get any on vacation either. After dinner my two younger siblings wandered away from the table to play with some of the children of the family but, as there weren't any children my age, I stayed at the table and listened to the adults talking. That is when one man asked my Dad the question—

Why to our Christian brothers and sisters in the United States hate us? I don't remember what my Dad's answer was—I don't think he was a fan of Christian Zionism even back then, so I imagine he did his best to regretfully explain a culture of largely uniformed religious ethnocentrism—and I don't remember the rest of the conversation. I think I asked my parents about it in the car on our way back to Jerusalem later because I was never able to be politically pro-Israel after that trip, and I have a vague memory of thinking that American Christians were "sort of confused" about the Middle East (a belief which was only reinforced when I began to attend bible college in South Carolina and found that telling people I had grown up in Turkey inevitably conjured up images from the film

Casablanca in their minds).

|

| You aren't going to convince me to hate Palestinians |

That was one family, one conversation. But it made its impression. It was a pebble rolling down the mountain and, once down, it could not roll back up the hill and regain its place. It was only a few years later that I became an Evangelical teenager in the late 90's (for those of you who shared that cultural moment with me, you will already know the weight of it, for those who did not, I will only say that it was both the heyday and swan song of American White Evangelical culture). I bought in almost to the hilt. I built a mental, religious, political, and philosophical structure out of the materials of late 90's White American Evangelical culture. Francis Schaeffer, DC Talk, the OC Supertones, True Love Waits, I Kissed Dating Goodbye, Quiet Times, Passion, Republicanism, Apologetics, the lot. My first vote was for George W. Bush and I worked my first job out of college to the sound of conservative talk radio.

But that structure had been built on an undermined foundation. That pebble (and others—they will have to wait for other blog posts) was missing. And I should say that it was consciously missing. I thought it gave me nuance. Knowing the kind of person I was in college, I probably thought it made me a little bit better than most of my peers. I understood that things were really more complex. But here is where that pebble really starts to make itself known. You see, the thing about having a pebble missing from under your foundation is that it is really difficult to just "let the empty space be" you need to fill it with something—I may be stretching this analogy too far, but work with me here—so you start to excavate the little hole. You study it, you dig around it, you try to figure our why the pebble that fell out of the hole didn't "work" there. This displaces more pebbles as you find that they don't really work either. Then you displace more pebbles.

Back in the real world (and away from pebble-analogy land) this excavation process really sped up after 9/11. I remember going online that night and somehow getting involved in a chat room (remember chat rooms?) where someone wanted "us" to "just go bomb the crap out of them" without any clear awareness of who "them" was beyond "middle eastern Muslims". I was somewhat horrified (remember that I have family and friends in a predominantly Muslim middle eastern country, and then that family in Bethlehem came to mind) and when I tried to push back I encountered the full, unveiled face of Christian American Nationalism. It was ugly, and more pebbles rolled down the mountain. See, it is hard to hate people you know. It is even harder to want the destruction of people who have been kind to you. It is harder than that to categorize as a "good" the mistreatment of people with whom you have identified—

our Christian brothers and sisters—and who have been kind to you. It is hard to support a structure which keeps telling you to be against them.

This is not the space for a full story of the deconstruction of my politically conservative Christianity; I hope to write my way through that in time. But from here I hope the outlines of the process have become clear. If religious political Conservatism was wrong about Israel then what else might it have been wrong about? And the "space" around the pebble grows... The questioning process, once properly begun, will not stop until it is frightened into remission, or has scoured the hillside down to the bedrock. In the end my trust in Jesus survived (

HERE is a series about what my relationship with Jesus looks like these days), my Christian Nationalism and religious political conservatism did not.