Imagine that Socrates, Peter Kreeft, and Jostein Gaarder sat down to write a book together. They might come up with something a little like Daniel Heck's According to Folly—at least, there are elements of this book which one can imagine each of them contributing. This book is in the form of an imagined series of conversations which a self-identified Fool has with a Conservative, a Liberal, and a Skeptic. On it's surface that premise is engaging enough in a straightforward "up the Moderates, and boo to polarization" sort of way; it is a premise which could be fairly compelling in the right hands or would, more likely, descend into nearly suffocating insufferability if executed poorly. Fortunately the book moves well beyond that surface premise by drilling down into the particularity of the author.

Imagine that Socrates, Peter Kreeft, and Jostein Gaarder sat down to write a book together. They might come up with something a little like Daniel Heck's According to Folly—at least, there are elements of this book which one can imagine each of them contributing. This book is in the form of an imagined series of conversations which a self-identified Fool has with a Conservative, a Liberal, and a Skeptic. On it's surface that premise is engaging enough in a straightforward "up the Moderates, and boo to polarization" sort of way; it is a premise which could be fairly compelling in the right hands or would, more likely, descend into nearly suffocating insufferability if executed poorly. Fortunately the book moves well beyond that surface premise by drilling down into the particularity of the author.In According to Folly, the respective Fool, Conservative, Liberal, and Skeptic are not the generic stereotypes of those ideologies as found in the contemporary Unites States—a move which would have doomed the project in the hands of any but the wisest and most well informed social critics. Instead Heck has written the characters as his Conservative, his Liberal, and his Skeptic (I will have more to say about the Fool below). The characters do not, therefore, employ the sort of straw man arguments one might expect. Instead they embody (one suspects) both the strongest and weakest of the arguments Heck has experienced in his own life. This is a critical move. The job of presenting the actual total arguments made by each of these camps would have been well beyond the abilities of any (almost any?) single author. What we get in this book instead is both much narrower and far more enlightening. Heck uses the person of the fool to socratically interrogate his own essential experience of these types.

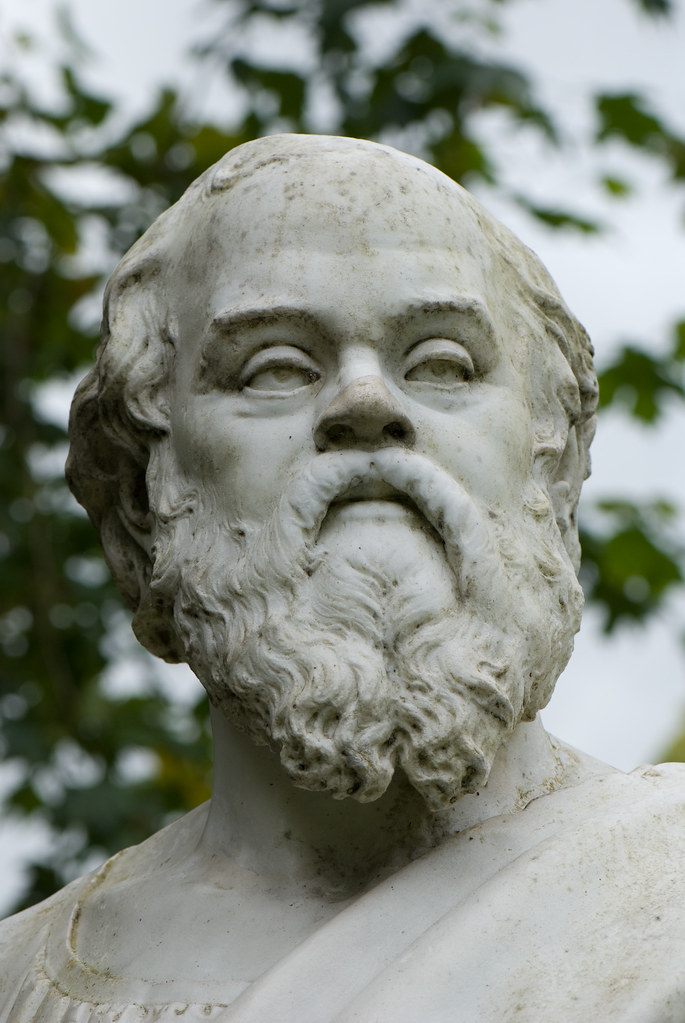

|

| Socrates |

It would be cliche'd to say that Conservatives, Liberals, and (Modernist) Skeptics will each love 2/3s of this book and hate the third which focuses on them; and while it may be true in some cases, I suspect that it is least true of the best of them. In fact I suspect that it is the wisest of our Conservatives, Liberals, and Skeptics who will enjoy this book the most. The temperament I believe least likely to appreciate this work is the person so committed to the rightness of his conclusions that he cannot bear to examine his own reasoning. It is the weak, rather than the strong and committed ideologue who will chafe, as this is a book which burns down straw men only so that the stronger ideas they hid can be revealed. C.S. Lewis wrote in his preface to Mere Christianity that

It is at her centre, where her truest children dwell, that each communion is really closest to every other in spirit, if not in doctrine. And this suggests that at the centre of each there is something, or a Someone, who against all divergences of belief, all differences of temperament, all memories of mutual persecution, speaks with the same voice.According to Folly adds further evidence to support his thesis.

No comments:

Post a Comment