This is the second post in a six part series. You can find Part 1, Solus Jesus is HERE.

The Blue Ocean Reflections series consists of my personal interaction and history with the six "distinctives" of the Blue Ocean Faith movement as laid out in the book of the same name (you can find my review of the book HERE). Throughout the series I intend to talk about my own history and journey of faith and to offer some thoughts on how what I have come to believe impacts my understanding of the world. As such this series is likely to have a heavy focus on theology, philosophy, and politics. But since my formal education has been as broad as I could make it, my reflections are apt to be fairly wide-ranging as well.

The second "Blue Ocean Distinctive" is their utilization of a centered set approach. Before I get into how taking a centered set approach to faith has affected my life and relationship to Jesus, let me get a big caveat out of the way: The theological take on set theory was first proposed by the missiologist Paul Hiebert of Fuller Seminary and was brought into the Vineyard movement by (I think) John Wimber. I do not know whether Schmelzer encountered it first through the Vineyard movement or from his own time at Fuller, but I first encountered it through a presentation he gave back when he was a Vineyeard USA pastor. Apparently the theological/missiological usage which has been made of centered set theory makes a total hash of the mathematical theories from which it derives its origin. I am totally fine with that as fidelity to the math is not at all necessary to the value of the framework as such, but I know it bugs some people so I want to acknowledge it.

OK, with that taken care of, let me open this piece by saying that centered set faith has been of incredible benefit me, spiritually and theologically (a distinction which will probably begin to make more sense in Part 3). Let me provide Schmelzer's outline of the idea, and then I will talk about the impact it has had on my thinking and end with a few of the modifications I have found helpful in thinking about the framework.

From Chapter 3 of Blue Ocean Faith:

...[P]icture two sorts of sets.

The first is represented by a circle. We'll call this a bounded-set. The issue with a bounded-set is with people being inside of the circle or outside of it.

The second, though, has no "inside" or "outside." Picture a large dot in the center of a page that has lots of smaller dots on the page as well. The issue here is motion. Are the smaller dots moving towards the center dot or away from it?Schmelzer goes on to clarify that the "center dot" in this centered set framework represents Jesus while the other dots represent individuals whereas in this analysis, the circle of the bounded set represents something like "being a Christian", "Chirstian culture", or "Christian identification" (it can actually be a lot of different things to different people). Later in the chapter he offers a refinement of the framework which he says he got from a friend named Dan:

But what, Dan suggested, if we all have more than one arrow? What if people are more complicated than that? What if we all have, say, a hundred arrows?and he goes on to talk about encounters which move some arrows towards Jesus.

For me, this idea has been incredibly helpful in thinking about spiritual and metaphysical realities and has also proved to be amazingly freeing. My own experience of faith has been pretty exclusively Christian, I was born in South Carolina to parents who were Evangelical Christians. When I was five, at a vacation Bible school meeting, I asked Jesus to forgive me for my sins (being then convinced that this prayer would result in Jesus choosing let me into heaven rather than allowing me to go to hell when I died—it seemed like a pretty solid deal to five year old me) and to "come into my heart" (and to this day I am convinced that that five year old did have an encounter with the living Jesus). When I was seven my family moved to Ankara Turkey where they quickly integrated into the Protestant ex-pat community and helped to start the International Protestant Church of Ankara. I returned to the US for college where I matriculated from an accredited Christian University in South Carolina (read "not Bob Jones") with a double major in Bible and the Humanities. And I have been a regular church attender my entire life. As a result, I have spent much of my life with an un-questioned sense of who is "in" and who is "out".

My basic, unexamined framework was bounded set.

I suspect that this is the case for a great number of Evangelical Christians; bounded set is the unexamined framework with which they categorize people—it may even be the primary framework they use. I am confident that this is the case for many at the conservative Christian university I attended. Before people are black, white, male, female, American, or anything else, they either are or are not "really" Christians. I remember talking to peers and faculty about the best ways to put words around the category of people who were "in"—should we talk about "those destined for heaven", was "Christians" too broad or too narrow, did baptism make a difference, etc...—just because that was the category which mattered most.

For a conservative Christian working within that framework, getting people over the line into the "us" is the most important thing in the world, and it comes with a whole lot of stress. Notice that in the refined centered set model, if an interaction results in one of either person's many arrows swinging at all in the direction of the center, the good outcome has occurred. To borrow language from another theological framework, insofar as arrows are moving towards Jesus, the Kingdom of Heaven is coming on earth. But in a bounded set framework, there is this line, and most of us were never entirely confident about where that line was exactly—though we were darn certain it was there and we had competing rough ideas of where "there" was—and getting people across the line was everything.

|

| You always felt that you might be this guy... |

This just isn't healthy, and there wasn't much of joy in it.

And there was another problem. In a bounded set world the critical thing, what really maters, is the boundary since that boundary is what determines (in most bounded set thinking) whether one spends eternity in heaven or in hell (I will have more to say about heaven and hell in another post). Those are incredibly high stakes, arguably the highest possible. The atheist magician Penn Jillette once explained that he sort of appreciates it when people try to convert him because it lets him know that they care about him enough to try to save him from the eternal fate they worry he is headed to; of course he disagrees but he definitely understands that their heart is in the right place.

The problem here is that the line is not Jesus. When we spend all of our attention on the line (and, lets face it, if bounded set is a good model and the stakes are as high as it would suggest then it is really hard to construct an argument for looking away from the line) we are, by that very fact, not looking towards Jesus. Jesus himself pointed out that it is impossible to serve "two masters" (he was talking about following either God or wealth when he made the statement but I think the principle applies more broadly), if the line becomes our master then Jesus is not.

|

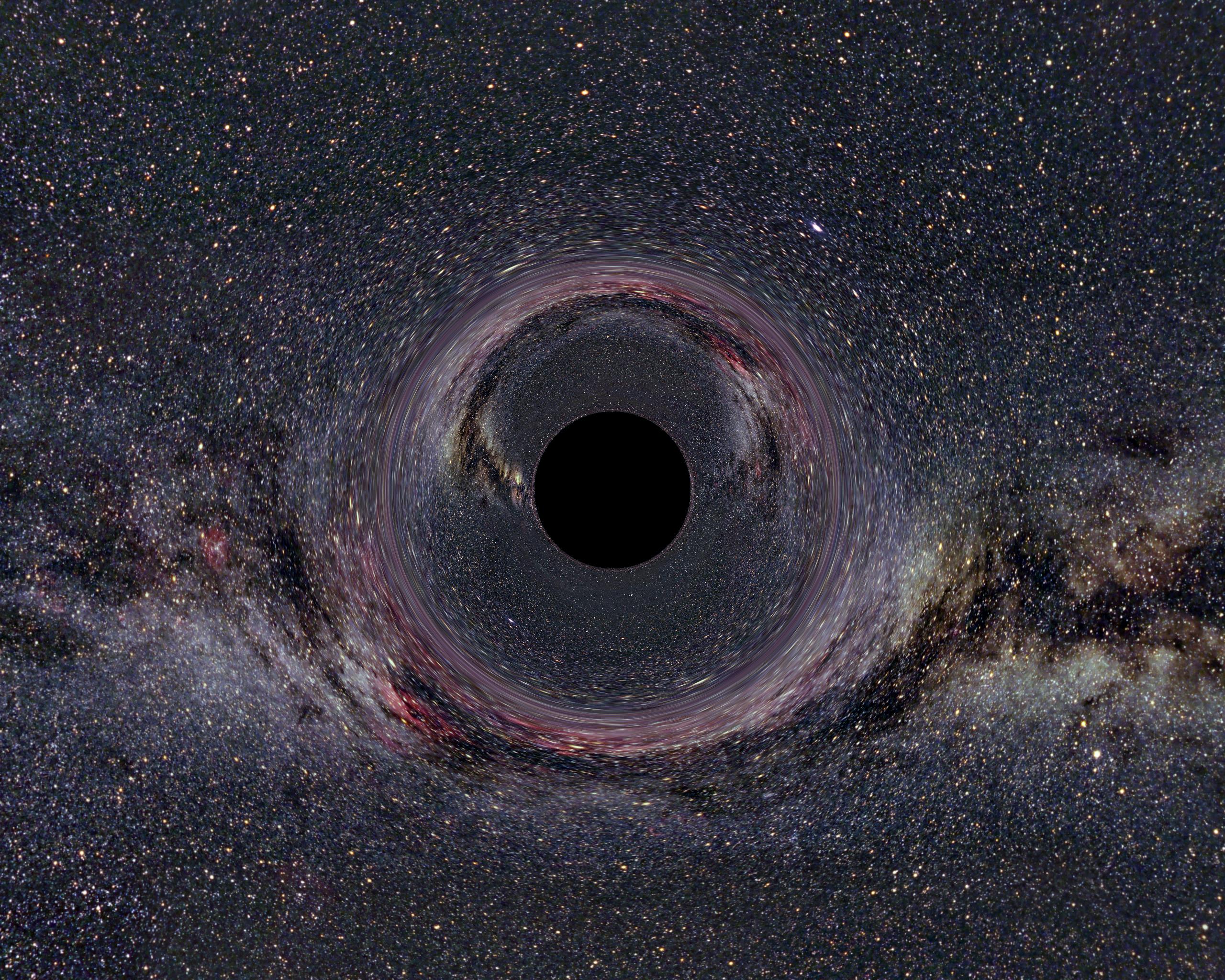

| Take a deep breath... centered set feels like this to me |

Side note: I have included one of my favorite TED talks below in case you are interested in thinking a little more about what successful discussions and even arguments might look like. It is by Daniel H Cohen and he breaks down the unhealthy, distorting ways we think about arguments. I can't recommend it enough

For all of that, I do have a few refinements of my own for how I think about centered set theory (I want to thank my friend Aaron Brooks for helping me with this one and suggesting key elements). I'll call it a Gravitational Centered Set while admitting that we are drifting really far from the original model.

I like to expand the picture from a set, to a physical scenario. So instead of a point with a bunch of other points moving around it, try imagining a black hole with all sorts of stuff orbiting it. In this iteration, Jesus is the black hole (yes I realize that our cultural associations with "black hole" are less than positive—just work with me here) and we are the particles flying around Him. In this iteration, everything is gravitationally drawn towards the event horizon of the black hole (after all Jesus did say that when he was lifted up he would draw all people to himself) but we also have a bunch of our own energy which we can use to try and break free of the orbit. The goal is still to be unified with the center (the black hole) and every interaction has the potential to further that progress. But here, without extreme effort on our part, being drawn into the goodness, love, and joy of Jesus is practically a sure thing—God claims to be about the business of rescuing all creation after all—and our "job" is to let it happen and not to give up on the process even when things get hard.

Also, I have been told that the closer you get to a black hole, the more things get weird. Looking back, the universe that made so much sense before starts to become distorted as light, time, and mass all start working differently, presumably we actually begin to see the goal itself more clearly. Also this process takes a long time (at least subjectively) but that is OK, God isn't short on time. I like this because I have found it to be true of my own relationship with Jesus. The closer I have gotten to him, the less the world which used to make sense, seems to actually cohere (I remember certain Pauline passages about the wisdom of God seeming like foolishness to people who aren't close to Jesus). It also means that getting everything "just right" isn't just implausible, it's a pretty foolish endeavor (though trying to improve our understanding to the best of our current ability is richly rewarding—it is always possible to have a better view even after you have given up on trying to claim you have the perfect view). Nothing outside the event horizon can see into the black hole. We aren't going to get some sort of perfect view of the center (I remember Paul saying something about seeing through a dim/distorted mirror for the time being) but the longer we look towards it and the closer we get, the better our understanding is likely to be. For me this has all had profoundly positive effects on my relationship with Jesus and on my interactions with my family, friends, neighbors, and even strangers. Strangers are a lot more compelling and fun when they aren't reduced to potential Evangelistic subjects.

So what do you think? I would love to get your thoughts in the comments section below.

For Part 3: Childlike Faith click HERE

|

| Click HERE to get Blue Ocean Faith on Amazon |

No comments:

Post a Comment