Good Manners

A man should drink

in moderation

be sensible or silent.

None will find

fault with your manners

though you retire in good time.

Self-Discipline

The glutton does not

guard himself

eats till he's ill.

Wiser men

only mock

a fool's fat belly.

Participation in online community requires listening as well as talking. Really successful "interneters" listen and engage rather than merely shouting and declaiming though there can certainly be a place for both of those things. I think there is a particular tendency to believe that in our own spaces (our blogs, our tweets, our Facebook walls) we have some sort of licence to be more rude than we would be in someone else's space. It is common to see people posting remarkably offensive things in their spaces and then defending those posts as unassailable due to a sort of perceived "right of self expression" or "freedom of speech". Of course, it is entirely true that they have a right to post what they like (remember that my basic working theory here is that online spaces are anarchic to nearly the same degree that Medieval Iceland was, if in its own way), but I believe that they are missing three important truths when they act this way.

First, they seem to be laboring under the misconception that civility exists as a discipline rather than as a virtue (I am, for the moment, ignoring those artists and philosophers who use shock value to communicate a point--they are another case altogether). In The Four Loves C.S. Lewis explained this well saying:

Second, the "fool" here, fails to realized that, online, even their "own" spaces are never really private. What is said online is said publicly. The advent of screenshots makes this particularly the case. In the case of the two largest social media platforms, comments, graphics, and memes posted on ones own "wall" (I use the term generically) are, absent particular privacy settings, going to be put directly into the feeds of other people who will then unavoidably react. Of course they may choose to react privately and not to comment, but that is no less a reaction. So it is basically untrue to believe that most online spaces are really "private" unless particular care is taken to ensure that the audience is limited and particular. Moreover, it has been my experience that the vast majority of people who hide behind the "it's my private space" claim have not actually engaged any privacy settings and seem to be intent on broadcasting the foolishness to as much of the internet as possible—they want the clicks.

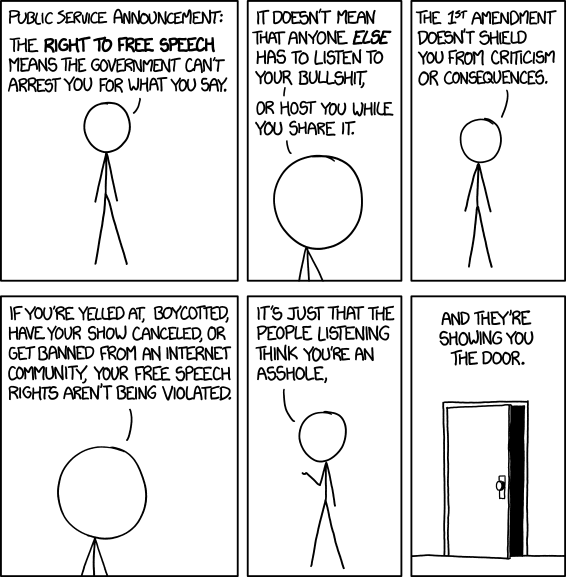

Finally, the defense commits the over-common mistake of conflating the freedom to say something with some sort of freedom from repercussions. Randall Munroe of XKCD put this most clearly.

The fact is that the freedom to spew foolishness does not, in any way, guarantee a protection from other people's reactions. In the anarchic environment of the internet (where rights are negative but almost never positive) it couldn't. You can be blocked, you can be screen-shot, you can be publicly ridiculed by those with more wit and intelligence than yourself. Your freedom to be publicly foolish, in no way prevents me from drawing the public's attention to your foolishness or from blocking your voice in my own sphere.

Click HERE for Part 12: Vulnerability

Note: This is part 11 in an ongoing series (the series starts HERE) bringing together the Hávamál (a collection of Norse wisdom poetry) and the still-evolving rules and mores of the Internet, particularly as they are developing in the realm of social media.

I characterize the Viking wisdom which emerges from these two poems as follows: "The internet is a community, not merely a platform and you ignore that to you own peril".

|

| Is this really what you want the world to see? |

First, they seem to be laboring under the misconception that civility exists as a discipline rather than as a virtue (I am, for the moment, ignoring those artists and philosophers who use shock value to communicate a point--they are another case altogether). In The Four Loves C.S. Lewis explained this well saying:

If you asked any of these insufferable people--they are not all parents of course--why they behaved that way at home, they would reply, 'Oh, hang it all, one comes home to relax. A chap can't be always on his best behaviour. If a man can't be himself in his own house, where can he? Of course we don't want Company Manners at home. We're a happy family. We can say anything to one another here. No one minds. We all understand.'

Once again it is so nearly true yet so fatally wrong. Affection is an affair of old clothes, and easy, of the unguarded moment, of liberties which would be ill-bred if we took them with strangers. But old clothes are one thing; to wear the same shirt till it stank would be another...Affection at its best practices a courtesy which is incomparably more subtle, sensitive and deep than the public kind. In public a ritual would do. At home you must have the reality which that ritual represented, or else the deafening triumphs of the greatest egoist present...

We can say anything to one another.' The truth behind this is that Affection at its best wishes neither to wound nor to humiliate nor to domineer.The enforced rules of civil society—rules which are unenforceable online—are there to impel those of us who have not yet acquired the virtues of civility to act as though we had nonetheless. At the end of the day, it is specifically in your own space that you will most often practice the civil virtues of moderation and sensibility exactly insofar as you posses them. And I think that people realize this on a fairly gut level. When we encounter someone who is rude, brash, and foolish in their own space, we are far more likely to be leery of their participation in other spaces.

Second, the "fool" here, fails to realized that, online, even their "own" spaces are never really private. What is said online is said publicly. The advent of screenshots makes this particularly the case. In the case of the two largest social media platforms, comments, graphics, and memes posted on ones own "wall" (I use the term generically) are, absent particular privacy settings, going to be put directly into the feeds of other people who will then unavoidably react. Of course they may choose to react privately and not to comment, but that is no less a reaction. So it is basically untrue to believe that most online spaces are really "private" unless particular care is taken to ensure that the audience is limited and particular. Moreover, it has been my experience that the vast majority of people who hide behind the "it's my private space" claim have not actually engaged any privacy settings and seem to be intent on broadcasting the foolishness to as much of the internet as possible—they want the clicks.

Finally, the defense commits the over-common mistake of conflating the freedom to say something with some sort of freedom from repercussions. Randall Munroe of XKCD put this most clearly.

|

| Taken from XKCD.com |

Click to get the Hávamál on Amazon

Click HERE for Part 12: Vulnerability

No comments:

Post a Comment