The cattle know

when to come home

from the grazing ground.

A man of lean wisdom

will never learn

what his stomach can store.

Happiness

He is unhappy

and ill-tempered

who meets all with mockery.

What he doesn't know,

but needs to,

are his own familiar faults.

Note: This is part 12 in an ongoing series (the series starts HERE) bringing together the Hávamál (a collection of Norse wisdom poetry) and the still-evolving rules and mores of the Internet, particularly as they are developing in the realm of social media.

As we have moved through the wisdom of the Hávamál it has become more and more apparent that virtue ethics, rather than a particular set of ethics rules, are the functional framework. The aphoristic poems don't so much tell the reader what action they ought to take in each and every situation as they lay out conditions under which particular virtues prove necessary. In that way they highlight those virtues which were most necessary to flourishing in a medieval (Viking) Icelandic society and are (by my hypothesis) also critical for online participation.

In these two poems, I would suggest that it is the virtue of vulnerability, or at least the virtue of an internal vulnerability which is being highlighted. In the first we get the pastoral image of a grazing cow, which knows when to stop eating and come in, applied to a man of "lean wisdom" who will "never learn what his stomach can store". In the second we get a reflection on the idea that an unwillingness to know your own faults can steal your happiness; or maybe it would be better to say that until we recognize our own faults, we will not be able to be happy. In both cases, we find that flourishing emerges from a lack of self-knowledge.

|

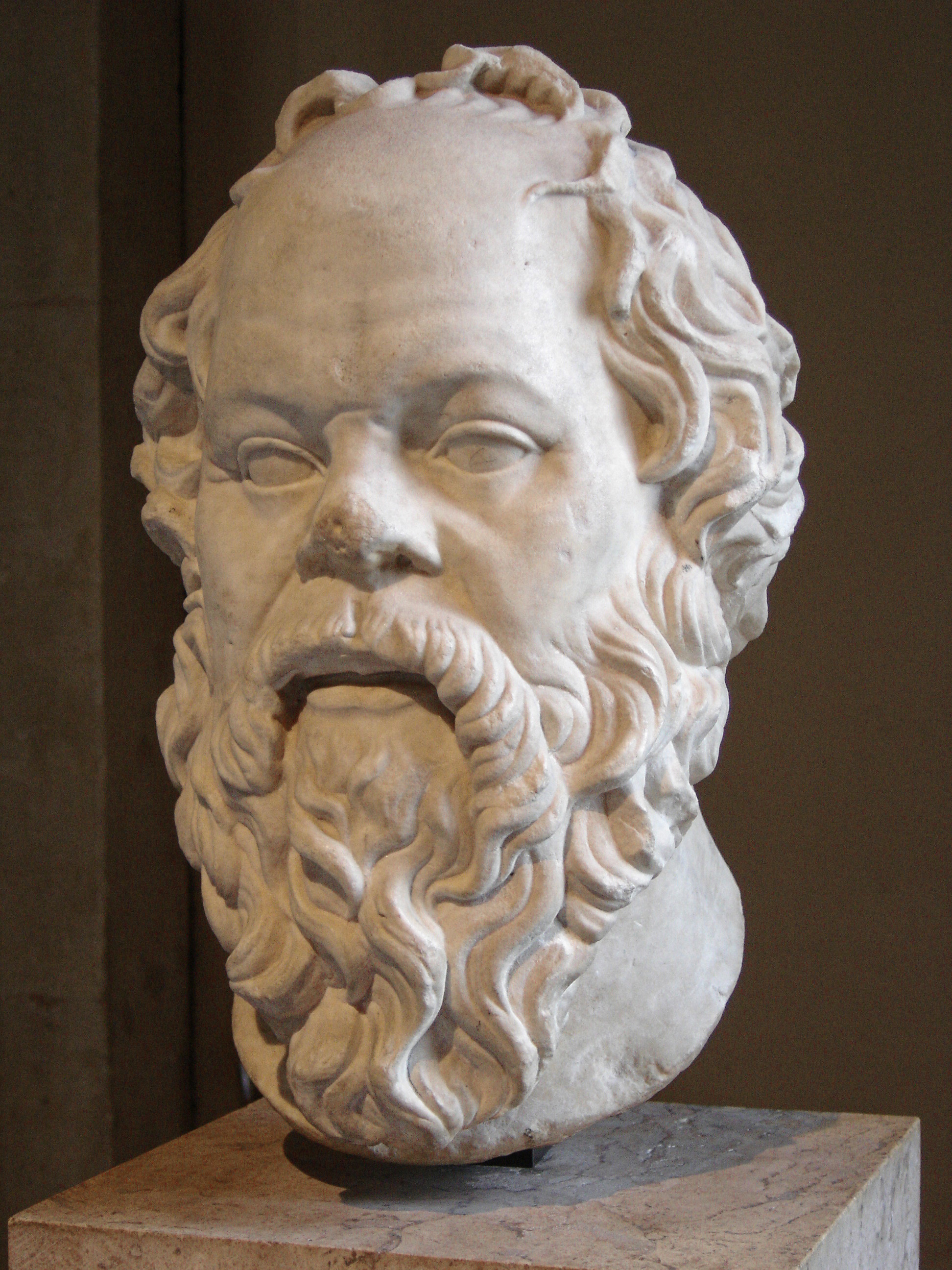

| Socrates |

Notably, this is a bit of wisdom which the Vikings have in common with Socrates and the Greek philosophical tradition. The aphorism "Know Yourself" (γνῶθι σεαυτόν) is said to have been etched over the doors of the temple of Apollo at Dephi—the structure which housed the Delphic Oracle. For Socrates the aphorism formed much of his motivation for engaging in philosophy and was also (if we are to believe The Apology) the clue to solving his ultimate riddle. The charge to seek out self-knowledge is a well established bit of wisdom.

And yet, it often seems to be lacking in our online engagement. There seems to be no end to the stories and studies on the way in which social media in particular, but cyberspace generally, has been isolating us in to ever-more polarized echo chambers. Generally the danger these stories and studies are working to point out is that closing ourselves off from dissenting opinion and an attendant decreased capacity for empathy with those outside our echo chambers, and that is a legitimate and weighty concern. At the same time, though I think it is also critical to highlight the way in which existing in an echo-chamber robs us of opportunities for self-knowledge. My Dad regularly points out that "It takes a non-parochial fish to know that it is wet", in other words, it is often hardest to see the very thing we are most surrounded by. In fact, the greatest opportunities we have to discover our own condition is the experience of encountering other conditions. Those experiences are what give us the opportunity to contrast our own "normal" with someone else's "normal". The best chance that fish has of recognizing its own wetness is if it begins to encounter air bubbles.

So too, when we find ourselves spending our time online, immersed in mono-cultural echo chambers, it becomes incredibly difficult for us to recognize our thoughts and approaches as anything but "the way things are" and, since we tend to seek out the most comfortable possible environments, we are particularly unlikely to be confronted with our own faults and weaknesses. The phenomenon of socio-cultural isolation and grouping isn't just bad for society as a whole, it stunts our growth as individuals (think about how much easier it is to think of yourself as a "rugged individualist" when everyone you encounter has your back anyway).

|

| A new environment can be...challenging |

But what does all of this have to do with vulnerability as a virtue (and for those of you who aren't sold on the idea that vulnerability isn't a virtue at all, I have included Brene Brown's excellent TED talk on the subject below)? As I understand it, vulnerability is a hybrid virtue combining love and courage. Vulnerability means loving the other (or the self) enough to risk being hurt while courage is the capacity to do what needs to be done. In this case we are being called to be vulnerable with our own selves. This critical virtue means first seeking out enough of an experience of the world that we are able to recognize ourselves, not as default humans, but as particular and unique beings (be like the cow and don't stop eating before you are full) and we have to take a good long look at that self which our experience has illuminated and risk the pain of seeing our own failings. In his essay On Forgiveness, CS Lewis points out:

Real forgiveness means looking steadily at the sin, the sin that is left over without any excuse, after all allowances have been made, and seeing it in all its horror, dirt, meanness, and malice, and nevertheless being wholly reconciled to the man who has done it.

I would suggest that that forgiveness critical when "the man" is myself. And it is vulnerability which empowers that forgiveness.

Resources:

If you are looking for ways to break out of—or at least recognize—your echo chamber, I ran into this tool from PolitEcho the other day which analyzes your FB feed and lets you know more about your political bubble. You might find it useful.

Brene Brown's talk on Vulnerability, she has also written a number of books on the subject:

Get the Hávamál on Amazon: